Recently, I read an article by Kent Beck over on Substack, in which he presented a 'Thinkie'—a small mind-opening idea—called Naive Solution. His idea is that if you're stuck, it can be valuable to pose the question:

Why is this any more complicated than [naive solution]?

At the end of the post, he asked people for concrete examples of this in real life, which is the reason for this post. I replied to Kent with an example I recently came across at work, and I reckon it's worth sharing in more detail here.

As mentioned in a previous article, I worked on a data pipeline in the complex railway domain. It consumed data from different sources and offered a canonical view of it. However, we soon realized that the source data might need corrections from time to time as there were problems with it.

When this was first discussed with the team, the goal was clear: add a way for admins to manually correct data after ingesting it from the source without tampering with the original data. However, what happened next was that people quickly, or perhaps in their enthusiasm or perfectionism, jumped to all sorts of elaborate solutions. One solution was a custom-built UI to edit the data, which the system would persist. Subsequently, each data pipeline run could read those files and use the data in processing. It was a viable solution, but the problem was that this solution clouded the problem statement.

Initial idea: not complicated, but could we achieve value in a simpler way?

At this point, me and a fellow team member started to ask questions about it:

What do we really want the user to accomplish?

What is the simplest thing we can do to add value?

Do we need all this right off the bat?

Above all, we tried to emphasize that we knew nothing about how often or how much the admins would have to rely on this feature—the churn in data was a big unknown. We started to push back and talked the feature down to its bare minimum.

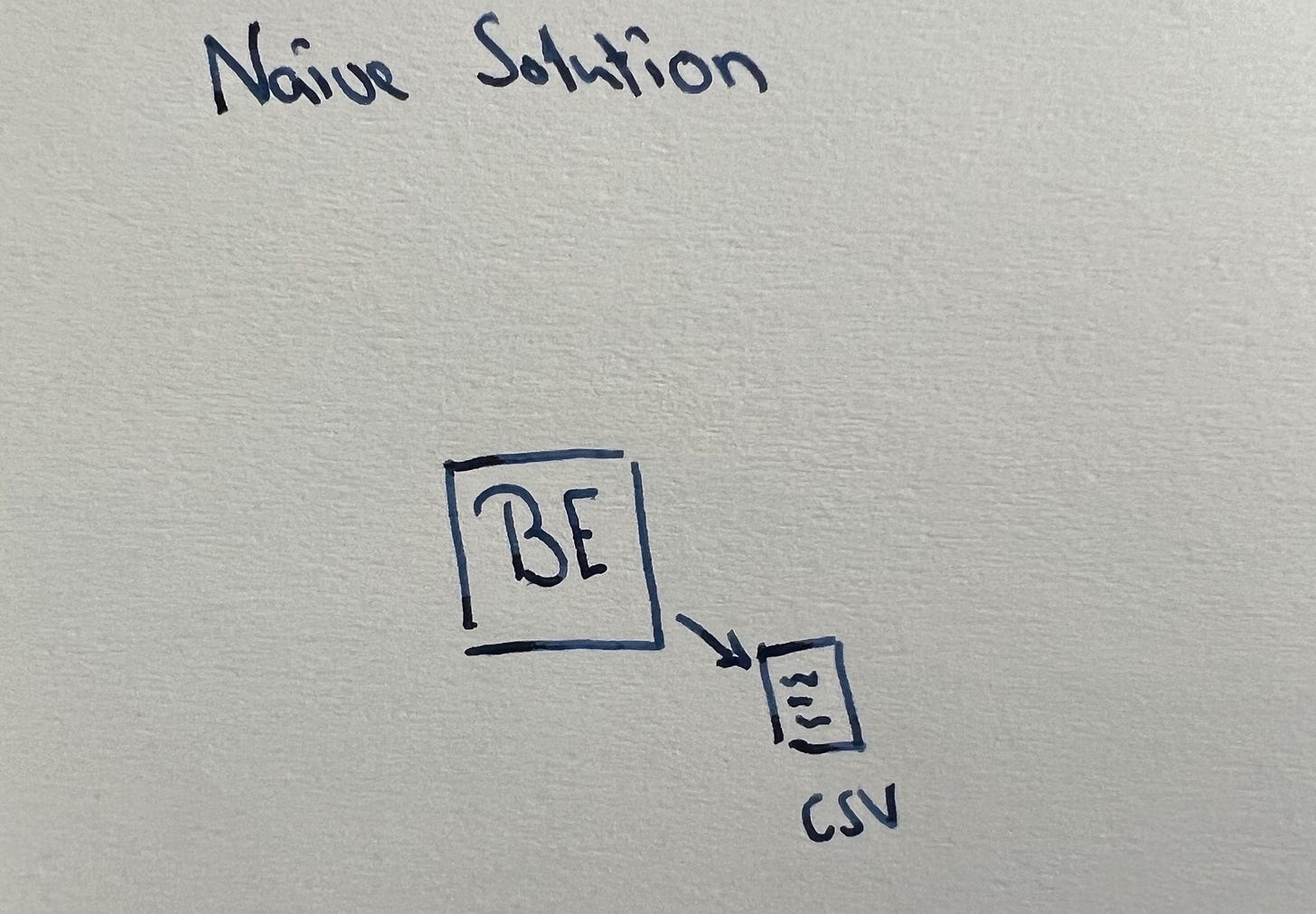

The solution we ended up with was minimal. We created the data corrections in a CSV file—great for data inspection and editing—and packaged it alongside the application. Each pipeline run could read the data from the resources folder and use it to correct matching data points. As always, there was a trade-off at play here:

Pro’s:

Simple. No need for custom UI/persistence mechanism.

Expandable if need arises. Big part of the mechanism is in place.

Data is traceable by piggybacking off Git.

Easily testable

Cons:

Deployment needed to update data.

Developer involvement needed to update data.

Not scalable to large amounts of data. Increases the JAR size and is stored in the Git repo.

Data inconsistencies. Each deployment carries it’s own data, thus multinode setups with rolling upgrades run the risk of using different data.

Naive solution: the bare minimum to evaluate whether the idea was valuable

Given the uncertainty, we wanted to conduct a low-effort experiment, so it seemed the right choice. Like I mentioned in the post of Kent:

Though the solution might be naive, asking these types of questions is not.

The naive solution we proposed was beautiful in its simplicity, setting us up for expansion but not investing more than strictly needed. We will simply invest more once friction increases to the degree that the feature becomes unpractical. What we did was eliminate waste.

Somehow, even though I know full well what Agile Software Development and Minimal Viable Products are all about, this experience was still eye-opening. It made me realize how many situations occur where you can try something with less effort. The art is in being able to spot them.

One of the easiest ways to make a big impact is what you describe here, in my opinion. Start asking why, and explore the minimalist route.